|

Joined:

|

28/09/2011 |

|---|---|

|

Last Updated:

|

31/10/2011 |

|

Location:

|

Beit Sahour, Bethlehem, Palestine, State of |

|

Climate Zone:

|

Mediterranean |

|

Gender:

|

Female |

|

Web site:

|

www.byspokes.org |

(projects i'm involved in)

(projects i'm following)

Posted by Alice Gray over 12 years ago

It was on the second week of the PermaNegev course that I arranged a visit to the small village of Herbaiet a Nabi in the south Hebron Hills. We were going to inspect the renewable energy installations put in place there by the Israeli NGO Comet-ME (www.comet-me.org), and to gain a better understanding of the politics of dispossession that form the ever-present background to the lives of the rural Arab communities of the Palestinian West Bank and the Israeli Negev. Since our focus for the week was ‘sustainable living: harvesting resources and managing wastes’, this fitted in well with the program, and was a great opportunity for students to see permaculture principles being applied on a number of levels, in a very challenging situation. As it turned out, the trip worked even better than I had originally planned, and gave much food for thought, some of which I am still digesting!

The residents of the village are cave-dwelling pastoralists, making their living by raising small flocks of goats and sheep on the sparsely vegetated hillsides surrounding the village and by cultivating small orchards of figs, grapes almonds and olives. They do not identify themselves as Bedouins, but as fellahin (farmers), and their lifestyle for generations has been sedentary rather than nomadic. Like many thousands of Palestinian residents of ‘Area C’ (which constitutes 60% of the land area of the West Bank) and Bedouin residents of the ‘unrecognized villages’ in the Negev, they are not connected to water, sewage or electricity grids; a situation that Oxfam has called “part of a systematic policy to push Palestinians off their land”. (1)

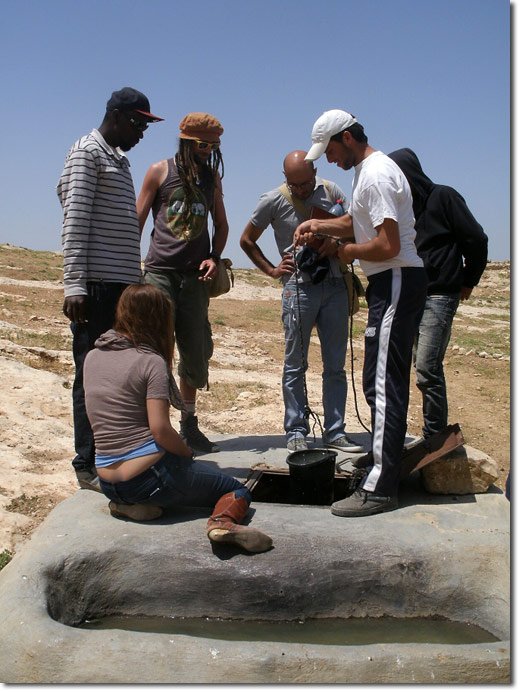

Comet-ME is an initiative to “build renewable energy systems for communities that are not connected to the grid because of political reasons and build local capacity to install and maintain these systems”. They work on the ethos that “access to energy services is a basic human right” and that “the provision of basic energy to the Palestinian population of Area C is not a security risk and must be allowed!”(2) We were lucky enough to get to meet with Elad Orian, co-founder and co-director of Comet-ME to get a briefing on the political and technical aspects of his work, before getting a tour of the village from Abu Brahim (the head man) and his sons.

Elad spoke to us about how he and his friend Noam founded the organization, progressing from participation in non-violent popular resistance activities (such as Bil’in weekly demonstration) to using their unique skills to support Palestinians in remaining on their land. As physicists they were able to develop hybrid solar and wind systems to provide electricity to ‘off-grid’ communities, setting up a workshop to build the wind turbines themselves and finding partners to supply the solar panels and transistors. He told us that setting up a system of this sort is only cost or energy effective where no other options exist, since it would otherwise be more economical to connect the communities to the existing energy grid.

He emphasized that in the case of the communities he works with, it is the responsibility of the Israeli government to provide these services, however they have chosen not to do so for political, rather than practical reasons (Herbaiet a Nabi for example lies between the Israeli settlement of Susiya and the southern checkpoint of the West Bank, very close to existing electricity lines). He also told us that 6 similar systems built by Comet-ME for other communities who are in the same situation have received demolition orders from the Israeli Civil Administration, and there is an ongoing legal battle to try to prevent the orders from being actioned.

This brought us on to a discussion of the institutional design of Comet-ME, which to me was even more interesting than the design of the systems themselves, and constitutes an aspect of permaculture that is perhaps under-discussed. There are several interesting aspects here. Firstly, the effort that is made to ensure local ownership of the systems through a) providing training in operation and maintenance, b) charging a tariff for the electricity at the same rate that grid-supplied people pay (the production cost is actually much higher if you take into account the cost of building the systems, so Comet-ME is subsidizing the communities, but this provides money for maintenance and upgrading plus ensures that the resource is respected and valued) and c) maintaining an ongoing relationship with every community served and upgrading the systems to keep pace with population growth, demand and technological advances that increase production and efficiency. This is the essence of good project design since the sustainability of the project is taken care of in environmental, social and financial senses.

Secondly, Comet-ME is committed to what Elad called a ‘lean NGO model’ – essentially ensuring that the vast majority of funding gained goes straight into building and maintaining systems rather than the running costs of the NGO. For example, they have never to date hired an office or a workshop, building wind turbines in Noam’s backyard and working from home, and have kept the number of paid staff to an absolute minimum, doing their own admin and reporting.

Thirdly, they have succeeded in giving their work not only practical but also political significance. Elad explained to us that Comet-ME had managed to get funding for many of their recent projects through the German Development Cooperation (GTZ) and thus were able to leverage support from high-level German officials to try to get the demolition orders overturned. Self-deprecatingly, he said that he couldn’t believe that “a pair of clowns” like himself and Noam had managed to get into a situation where the German Minister for the Environment (Peter Altmeier) was discussing their project with Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak during his last visit to the Middle East. Of course, the issue of the energy systems is part of a much broader issue over whether the communities involved will be able to stay on their land and maintain their way of life – a question that beats at the heart of permaculture worldwide.

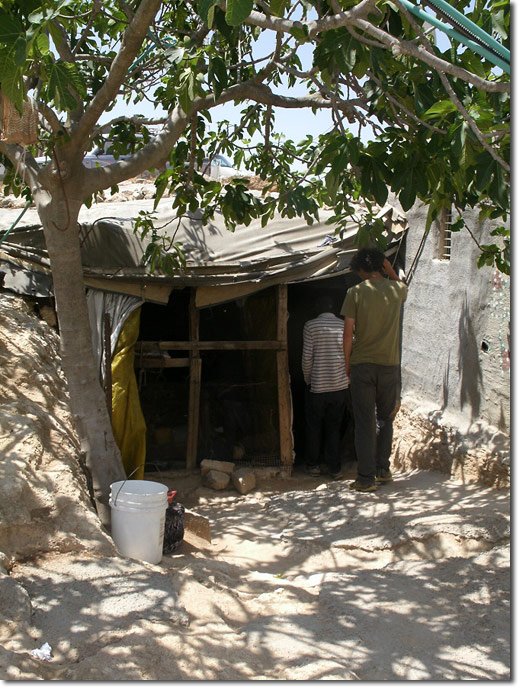

A review of the next stage of our visit will illustrate what I mean. After taking in an epic lunch of fresh baked bread, olive oil, buttermilk and salads we went for a tour of the village, to see the rainwater harvesting systems, the orchards and the ancient caves. What was manifestly obvious on this tour was that this community lives in an intimate relationship with the environment around them, generating their own resources and making good use of much of their ‘wastes’. For example, the bread we ate at lunch-time (a delicious yeasted brown flat-bread called ‘taboun’) is cooked in a stone built oven fuelled with dried goat manure (zibbl). The people live in ancient caves in the side of the mountain, which offer excellent insulation: cool in summer and warm in winter, and minimize consumption of building materials. Rainwater is collected in new and old pear-shaped cisterns (bir anjas) and used for cooking, washing and watering the animals. Chickens, goats and sheep throng the village and the outer caves.

More so than the vast majority of Westerners or people living in cities worldwide, these people are living a sustainable lifestyle and have a high level of environmental awareness. Yet if plans to force them off their land go through, they will join the hoardes of people on the planet who have no control over their relationship with the environment and contribute every day to the status quo of environmental destruction that accompanies urban lifestyles: eating industrially produced food in throw-away packaging, dependant on fossil-fuel sustained agriculture, joining the urban proletariat working in factories or quarries, building Israeli settlements or working in Israeli agro-industrial enterprises (if they could find work at all which is doubtful in the West Bank where unemployment stands at over 20%). In any case, this sort of forced transfer in an age of peak oil and energy descent strikes me as analogous to standing on the deck of the Titanic as it sinks and blowing holes in the lifeboats.

The whole thing smacks of the kind of arrogant cultural imperialism, blind technocracy and outright colonialism that has seen indigenous people all over the world displaced from their land and their cultures destroyed. Writing in 2010, the UN stated:

Despite all the positive developments in international human rights standard-setting, indigenous peoples continue to face serious human rights abuses on a day-to-day basis. Issues of violence and brutality, continuing assimilation policies, marginalization, dispossession of land, forced removal or relocation, denial of land rights, impacts of large-scale development, abuses by military forces and armed conflict, and a host of other abuses, are a reality for indigenous communities around the world. Examples of violence and brutality have been heard from every corner of the world, most often perpetrated against indigenous persons who are defending their rights and their lands, territories and communities.(3)

Unfortunately, in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, it is getting worse. Depopulation in Area C of the West Bank is rampant. For example, the population of the Jordan Valley is estimated to have fallen by over 75% since the occupation began in 1967, and of those residents remaining, over 70% live inside the city of Jericho.(4) According to figures obtained from the UNOCHA working group, 1072 structures were demolished by Israeli forces between January 2009 and July 2011 (275 in 2009, 439 in 2010 and 358 in the first 6 months of 2011). Structures included houses, schools, animal shelters, toilets, water cisterns, playgrounds and mosques. These destructions lead to the displacement of nearly 2000 people and further affected more than 16,000.(5) According to a report by the Negev coexistence forum, demolitions in the unrecognized Bedouin villages in Israel more than doubled in 2011, when over 1000 structures were demolished.(6) Currently, the entire Palestinian village of Susiya in the West Bank is under threat of demolition, and just this week the Civil Administration announced that they intend to demolish a further 8 villages in the same area to make way for a military training ground.(7)

The work of organizations like Comet-ME is a great example of the kind of design we need in permaculture to control against the erosion of human cultures and human rights as surely as we need to control against the erosion of soils and biodiversity. In fact, a recent study has linked the loss of global biodiversity to the loss of human cultural diversity, pointing out that “it may well be that biodiversity evolved as part-and-parcel of cultural diversity, and vice versa”, and that “people are part of ecosystems”.(8) After all, these cultures may well be our lifeboats to a sustainable world!

We will be running two more 6-week courses out of Qasr A Sir Ecokhan, starting on August 26th and October 7th this year. It is a great opportunity to throw yourself in at the deep end of what permaculture can mean, politically, culturally and environmentally and places are still available! The course will include visits to Bedouin villages, Palestinian farmers, ancient Nabatean ruins, Israeli kibbutzim and much more!

Find out more about the course and register.

References:

You must be logged in to comment.

| Australian-Palestinian Permaculture Design Course |

| Type: Permaculture Design Certificate (PDC) course |

| Verifying teacher: Brad Lancaster |

| Other Teachers: Murad J.R.ALkhufash, david spicer |

| Location: Marda Permaculture Farm, Salfit, Palestine |

| Date: Jun 2010 |

| 10 PDC Graduates (list) |

| 0 PRI PDC Graduates (list) |

| 0 Other Course Graduates (list) |

| have acknowledged being taught by Alice Gray |

| 0 have not yet been verified (list) |

| Alice Gray has permaculture experience in: |

|---|

| Mediterranean |

| Arid |

| Semi Arid |

| Hot Desert |